The blood, sweat, and raw insanity it takes to drag even a terrible movie into being would snap most people like a breadstick. And yet, some films vanish before they’re ever seen - derailed by greed, stupidity, or the cruel whims of the Movie Gods. They haunt us from beyond the grave, lingering in a spectral blur of rumors and what-ifs.

Today, we honor five of them.

5. Kaleidoscope (1967, Alfred Hitchcock)

Inspired by trashy, blood-soaked Italian giallos and Antonioni's Blow Up and Red Desert, Alfred Hitchcock set out to make his most graphic and depraved movie yet - a story told through the eyes of a necrophiliac serial killer. The script shocked Hollywood producers. Not even François Truffaut, Hitchcock’s bon ami, could stomach it.

But Hitch was hellbent. He relocated to New York to plot out the murder scenes - one in Central Park obviously, another on a mothballed battleship. He brought in a flurry of writers, including British playwright Benn Levy, Howard Fast and Hugh Wheeler, then hired Arthur Schatz, gathered a handful of actors, and started shooting. Though about an hour of footage exists, Universal executives declared the project dangerously uncommercial, and persuaded Hitchcock to abandon it in favor of Topaz, a film that, to this day, excites absolutely no one. “This footage… is an incredible glimpse into what could have been,” lamented Hitchcock biographer Dan Auiler. “Hitchcock would [have] re-emerged at this late point in his life at the forefront of style.”

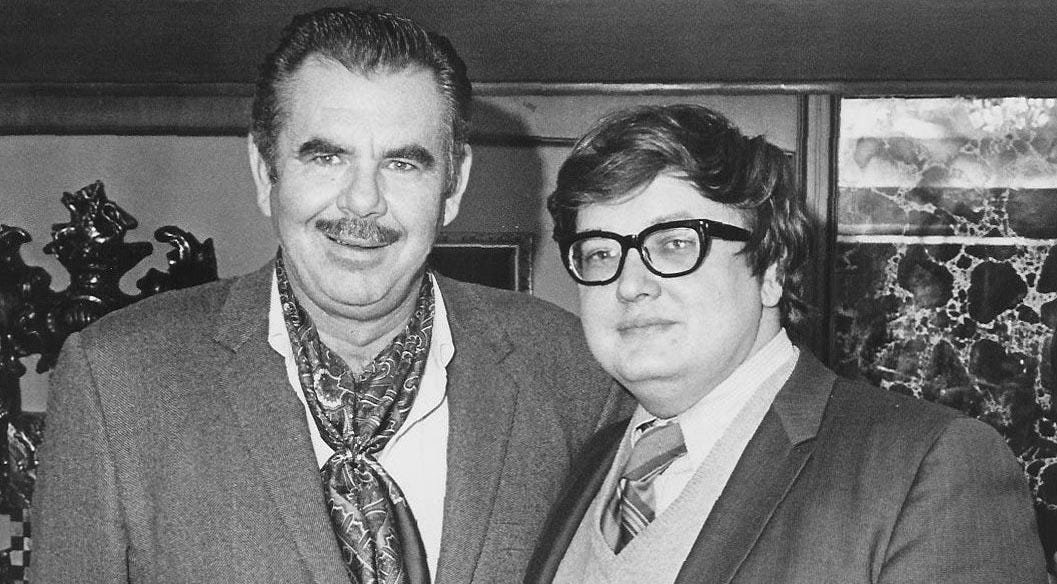

4. Who Killed Bambi? (1977, Russ Meyer)

At the height of their notoriety, British punk chaos agents The Sex Pistols embarked on a big screen project - an anarchic, X-rated answer to A Hard Day’s Night. And who did their infamously scheming manager, Malcolm McLaren, tap to bring it to life? None other than Russ Meyer, the grand wizard of flamboyant, breast-centric sexploitation, and Pulitzer-winning film critic Roger Ebert - yes, that Roger Ebert - who had a side hustle as Meyer’s screenwriter - yes, really.

McLaren called for a riot on celluloid, a cinematic Molotov cocktail that would announce the Pistols to the American market. Filming began in London in October 1977, but true to the Pistols' brand, imploded spectacularly after just a day and a half. 20th Century Fox, horrified by the filth and mayhem unfolding, yanked the plug. Who Killed Bambi? existed only as rock doc folklore until 2012, after McLaren’s death, when Ebert published the full screenplay on his website “for the benefit of future rock historians.”

3. Something’s Got to Give (1962, George Cukor)

Ellen Arden, a photographer and mother, was lost at sea in the Pacific, and declared dead. Five years later, she is rescued from an island and returns to her husband Nick, who has just remarried. Hilarity and skinny dipping ensues.

Something’s Got to Give was just another breezy studio sex comedy, a remake of 1940’s My Favorite Wife, this time starring Marilyn Monroe and Dean Martin. But the trouble on set began immediately. Monroe, who hadn’t shot a film in 18 months, was battling sinusitis, depression (she had recently been hospitalized for it), and a fiendish barbiturate addiction. She showed up for only 13 out of 30 shooting days before she was fired for “spectacular absenteeism” and sued for $750,000 for violating her contract. Fox attempted to recast her, but Dean Martin refused to work with anyone else. Fox then scrambled to hire Monroe back, and a deal was struck to resume filming in October. But in August, Monroe - tragically - died of an overdose.

The production was scrapped, and the film was thought to be lost forever, until nine hours of dusty raw footage was discovered in a warehouse in 1989. You can catch a glimpse of the unfinished romp here.

Underexposed is an independent, ad-free, weekly publication fueled entirely by the support of readers like you. If you believe in the power of art, creativity, and the ritual of moviegoing, consider upgrading to a premium subscription. Not only will you help me build a future that celebrates cinema, you’ll also gain access to exclusive bonus articles and videos.

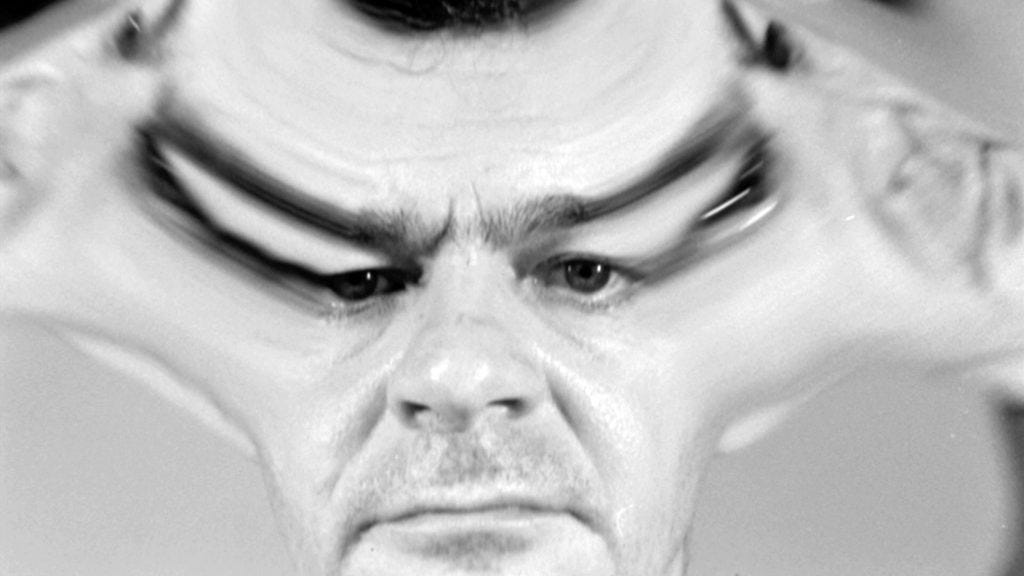

2. Inferno (1964, Henri-Georges Clouzot)

Inspired by the acid-washed visuals of experimental cinema, Henri-Georges Clouzot set out to make Inferno, a frenzied descent into jealousy and madness. Middle-aged hotelier Marcel (Serge Reggiani) loses his merde when he starts to suspect his beautiful 26-year-old wife, Odette (Romy Schneider) is cheating on him.

Armed with a blank check from Columbia Pictures, Clouzot enlisted three crews and 150 technicians to realize his vision. Sadly, the project was hexed from the start. Record heat dogged the production. As Clouzot’s perfectionism spiraled into unchecked indulgence, Reggiani faked illness to quit the film. The central feature of the resort location, a lake, was suddenly ordered to be drained by local authorities. Clouzot pressed on - until a heart attack finally brought him to his knees, grinding the runaway production to a halt.

The shards that remain are hypnotic, nightmarish, and peak gif material. You can catch a longer glimpse in the 2009 documentary Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Inferno. “The fragments we have are stunning,” said the filmmaker Serge Bromberg. “Had Clouzot finished Inferno, it might have rewritten the language of psychological horror.”

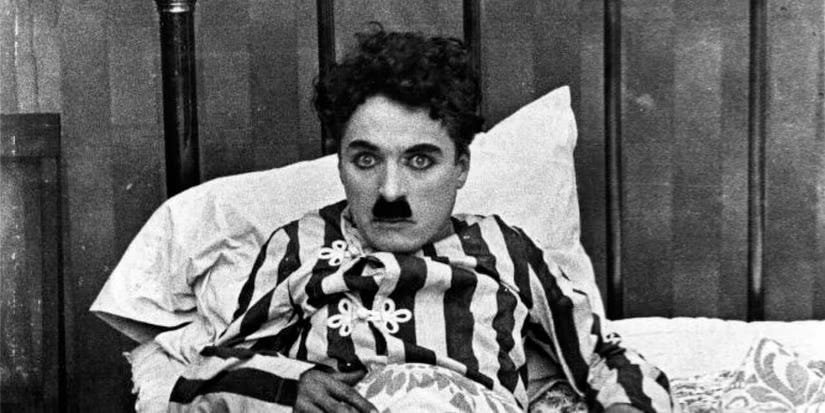

1. A Woman of the Sea (1926, Charlie Chaplin)

A Woman of the Sea died the cruelest death of all: its reels were burned - intentionally - by Charlie Chaplin himself.

In 1926, Chaplin, at the height of his stardom, agreed to fund A Woman of the Sea, a passion project from director Josef von Sternberg. Starring Edna Purviance, Chaplin’s longtime leading lady and former romantic partner, the film was envisioned as a moody, starkly poetic drama set in a coastal fishing village, contrasting the lives of two sisters - one wild and free-spirited, the other dutiful and restrained.

Despite von Sternberg's ambition and Purviance's hopes of reviving her career, the movie never saw the light of day. After a test screening in Beverly Hills garnered poor reactions, Chaplin deemed it unreleasable. To mitigate the losses, he gathered five witnesses and burned all the negatives to secure a tax write-off.

Though this tactic of deliberately destroying a film for financial reasons was rare at the time, it’s kind of a vibe now. Chaplin never spoke much about A Woman of the Sea again. For von Sternberg and the rest of us, it’s just a ghost - forever lost to the flames.

And now, this week’s Underexposed Movie Pick -

L’Enfer (1994, Claude Chabrol)

Sifting through the ashes of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Inferno, Claude Chabrol retrieved the script and set off to make L'Enfer (Hell) with François Cluzet and Emmanuelle Béart three decades later. Stripped of Clouzot’s hallucinogenic flourishes but rich in Chabrol’s house mix of bourgeois tension and jangling paranoia, the film follows a man consumed by jealousy, unraveling as he becomes convinced his younger wife is infidèle. Chabrol’s L’Enfer stands on its own as a tightly wound, quietly devastating thriller, with a masterful use of time distortion that I’ve seen nowhere else. The way he bends time until screen minutes stretch slower than reality is a brilliant, pulse-quickening technique. Currently streaming on Roku and BFI Player Classics via Amazon.

News Reel

- weighs in on the rank stupidity of the Disney Snow White discourse, and its troubling implications: “The narrative of our entire industry is consumed with finger-pointing nonsense, turning us against each other in silly spats when we should be focused on restoring some meaning and excitement to what we do.”

- weighs in on the death of weirdness in film: “I think a lot of folks claim to dislike experimental film because it often lacks perceivable plot and therefore what they call ‘substance,’ but what they are unaware of is that a radical assault on traditional storytelling conventions is an assault on the status quo, on the bourgeois expectations western audiences often hold when they watch a movie. Become aware of convention, break standards. Like, if you’re working on an indie production right now, you should be thinking about how the film can break conventions rather than conform to them. I see a lot of contemporary indie films that use Save the Cat narrative formats or employ the most generic methods of cinematography and editing (especially for dialogue scenes), and I always wonder why. Where is the drive? Where is the desire to break free of convention, the same one that allowed every filmmaker we admire to rise above the norm? Make art, not resume pieces.”

- is back with a sharp and deeply personal reflection on the film Margin Call and our current crisis: “Margin Call exists as that rare cinematic chimera - gothic horror masquerading as boardroom procedural. Kill the soundtrack and behold pure existential panic in bespoke suits. Some executives frantically calculate survival odds. Others quietly liquidate personal holdings. Then comes that odd subspecies of corporate fauna insisting the building remains structurally sound while their Italian loafers literally smolder.”

That’s all for this week’s free edition. Beyond the paywall, we have a bonus segment, Fever Dreams - a look at three more lost films, including an unrealized collab between Salvador Dalí and the Marx Brothers, a sci-fi epic that would’ve been the first ever animated feature film, and a Fellini fiasco. Join us!

Fever Dreams

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Underexposed to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.