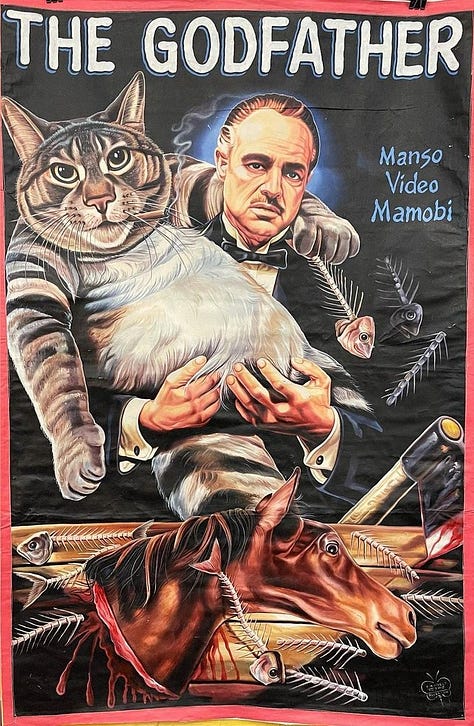

Untamed Art: The Glorious Madness of Bootleg Ghanaian Movie Posters

In the '80s and '90s, traveling cinema clubs brought Hollywood movies to rural Ghana, where local artists painted posters for them. It sparked a global sensation.

It’s 1985, and you’re a goat farmer in rural Ghana.

You’re sitting in the flickering shade, the dry breath of the Sahara on your neck, millet whispering in the wind. Behind you, the low murmur of the village - women pounding fufu in wooden mortars, the distant crack of an axe splitting firewood. The sky is vast and unbroken.

Then, a sound. An engine, coughing and spitting dust down the red-dirt road. A battered truck lurches into the village square. The Cinema Club has arrived.

That night, the whole village gathers around a shimmering screen to watch a sneering man with a bandana and a machine gun. “Rambo.” His muscles twitch. His eyes burn. Goats stir in their pens, restless. Nothing will be as it was.

The Dawn of Ghanavision

The rise of home video brought movies to the most remote corners of western Africa. Mobile cinema operators crisscrossed the countryside, screening films in churches, homes, and open-air markets. To draw crowds, they needed eye-catching advertisements. But there was a problem: Ghana’s military government forbade the import of printing presses. So the mobile cinema operators turned to local artists, most of them self-taught sign painters.

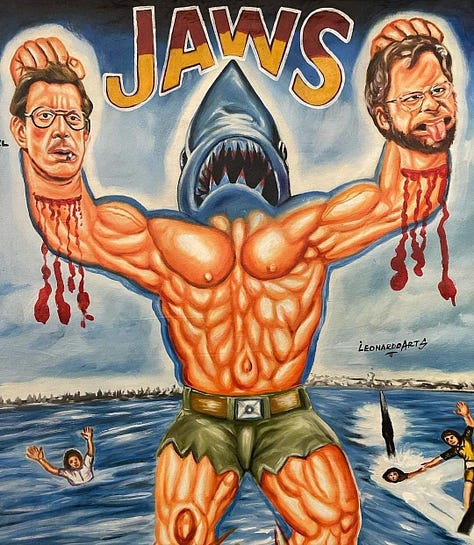

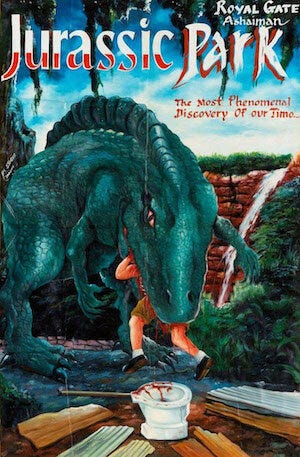

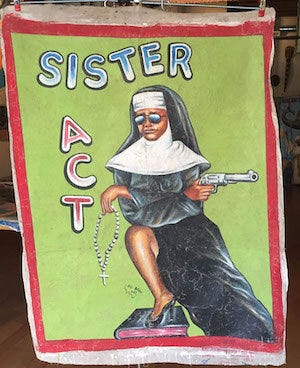

Some had not yet seen the movies, while others had a selective regard for the characters and plots - adding guns, gore, and other salacious embellishments to lure audiences. Using recycled flour sacks as canvases and a mix of house and oil paints, they unleashed their eye-popping visions.

With the rise of the internet, cinema clubs faded away, and so too did the demand for hand-painted Ghanaian movie posters. Or so it seemed.

5,700 miles away in Chicago, Brian Chankin was running a tiny underground video store when a friend handed him a book called Ghanavision, a tribute to the obscure art form. He was mesmerized. Chankin started collecting the posters and hanging them in his shop. Customers clambered to buy them. As demand grew, Chankin decided to track down the artists.

In Accra, Ghana, he partnered with Robert Kofi, a shop owner and talent agent to several of the movie poster painters. Together, they founded Deadly Prey Gallery, dedicated to celebrating Ghanaian movie art. Over the next decade, they expanded their roster, working with legendary artists like Heavy J, Farkira, Salvation, Stoger, Mr. Nana Agyq, C.A. Wisely, Magasco, and H.K. Mathias. “We’re able to pay them incredibly well,” Chankin said. “I don’t even want to tell you what these guys were making originally when they were painting for the video clubs. It wasn’t good. We’ve been able to get them better money and change situations.”

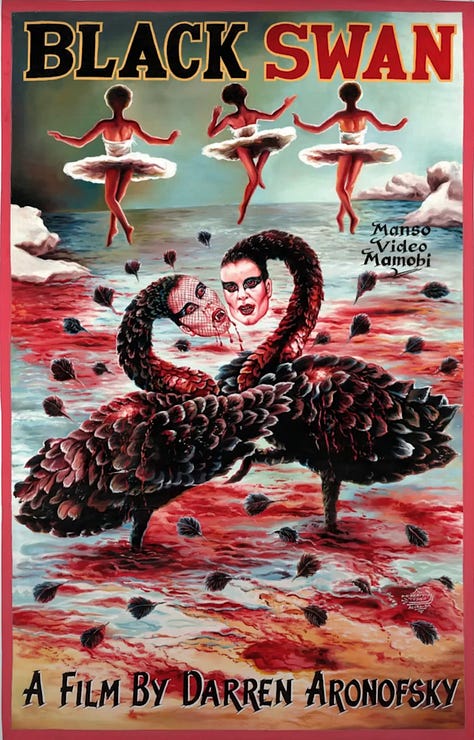

The posters began appearing in art galleries worldwide, and collectors started commissioning custom works. Filmmaker Darren Aronofsky personally commissioned posters for every one of his films.

Today, the popularity of Ghanaian movie poster art continues to spread on social media, and what began as a fringe relic of Ghana’s DIY cinema scene has blossomed into a global art movement. In a world dominated by sanitized, mass-produced imagery, these hand-painted works are a rare, balls-out bacchanal of artistic vision - bold, nightmarish, and bursting with unhinged brilliance.

Underexposed is an independent, ad-free, weekly publication fueled entirely by the support of readers like you. If you believe in the power of art, creativity, and the timeless ritual of moviegoing, consider upgrading to a premium subscription. Not only will you help build a future that celebrates cinema, you’ll also gain access to exclusive bonus articles and videos. Your support makes all the difference.

News Reel

A glimmer of good news from the UK’s boutique cinema chain Everyman - revenues are up 17.9%, with two venues to open in 2025.

In the New Yorker, Namwali Serpell bemoans the new literalism plaguing today’s biggest movies. “It’s hard to say which came first: our so-called media illiteracy or the dumbing down of the media. Complaints about our inability to read, interpret, or discern irony, subtlety, and nuance are as old as art. What feels new is the expectation, on the part of both makers and audiences, that there is such a thing as knowing definitively what a work of art means or stands for, aesthetically and politically. This strikes me as a blatant redefinition of art itself.”

- from the reflects on New Romanticism and cinema, and what Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s novel Demons and its chilling forecast for our times: “As Americans, we've been raised on [Jane] Austen-like narratives of redemption. But have you noticed that our contemporary narratives of success and romance have become increasingly err… Russian?”

“Where Is Hollywood's Money Going?”

tackles the problem of ever-inflating movie budgets: “I’d rather have sixteen A24 movies than one Red One. It’s time for the big studios to wake up, do the math, and realize that this boom-or-bust business model isn’t sustainable. You can’t have one Oppenheimer for every ten box office bombs and expect to stay in business.”

And now, this week’s Underexposed Movie Pick:

Mandabi (1968)

Satire is like cilantro - a little goes a long way, and its flavor can easily overpower. Ousmane Sembène’s Mandabi is what I would call a perfectly seasoned satire. The film follows Ibrahima, a fidgety, status-conscious (and currently unemployed) man in Dakar who receives a money order - an unexpected remittance - from his nephew in Paris, who has been working as a street sweeper. What should be a blessing quickly becomes a burden as Ibrahima sets out to redeem the money, and is instead pulled into a farcical web of postcolonial bureaucracy and regional corruption. Meanwhile, word spreads and friends and neighbors circle, eager for their share.

The film fizzes with levity, almost like a Preston Sturges comedy, yet it remains a deeply political work. Characters speak mostly in Wolof - it was the first African feature film made in a native language rather than a colonial one. Each frame is rich with sly details, like the cheap plastic Caucasian baby doll that appears in shot after shot. Mandabi is a black comedy of errors and terrors, where even the smallest shred of hope is strangled by red tape, and everyone’s after a piece of the pie.

Where to watch Mandabi

Currently streaming on the Criterion Channel.

Also available on disc.

That’s all for this week’s free edition. Paid subscribers, join me in the “VIP” for a bonus segment, Bombay Video Library - A Ghanavision Cinema Club Mixtape.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Underexposed to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.