What is Film School For?

Featuring Directors GARY O. BENNETT and ALYSSA RALLO BENNETT of NYU Tisch Drama Residency STONESTREET STUDIOS

It’s Valentine’s Day! Or, as it’s known in the DOGE era, Love Tax Season - a mandated day to settle emotional debts with chocolate and flowers, and decide if our romantic partnerships are still in alignment, or due for restructuring.

Since we’re in the mood for love audits, let’s talk about film schools. Are they still “worth it” in 2025?

It’s a valid question. We live in an era when our phones shoot 4K and YouTube tutorials are free. The film industry is buckling, AI is looming, and the kids are watching TikTok, not Tarkovsky. Is there still value in a formal film education?

I believe so - and perhaps more than ever.

To make my case, let’s first go back to the beginning, and meet the founding father of film schools - Vladimir Lenin. Yes, that Lenin.

A Revolutionary Experiment

On October 25, 1917, in St. Petersburg, Russia, Lenin led the Bolsheviks to victory in an armed insurrection, kicking off the Soviet era. Two years later in Moscow, he authorized the creation of the world’s first film school: The All-Union State Institute of Cinematography (VGIK). “The cinema is for us the most important of the arts,” Lenin declared, recognizing the new medium’s potential to reach massive audiences without the requirement of literacy. He would’ve been a great studio exec.

There was just one problem: The school had no cameras or film stock. Pre-revolutionary producers had mostly fled, destroying their studios and taking their equipment with them. A foreign blockade prevented new imports. But the Russians would not be deterred.

After obtaining a print of D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance, film teacher Lev Kulesov screened it repeatedly for his students, ordering them to memorize its shot structure and plan their own films (on paper). Out of this rigorous study grew the theories of montage and what we still know today as the Kulesov effect - or how the meaning of a shot changes based on the shots that follow or precede it. Some of Kulesov’s earliest students, like Sergei Eisentstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin, went on to become early masters of cinema.

Hollywood’s Backyard

A full decade after VGIK and six thousand miles away, the first American film school was founded at the University of Southern California in 1929. Unlike VGIK, which was state-controlled and ideologically driven, USC had a close relationship with Hollywood studios, emphasizing industry connections and professional training. Guest lecturers included Douglas Fairbanks and D.W. Griffith.

Through the end of the 20th century, film schools proliferated, and with them, influential directors like George Lucas (USC), Charles Burnett (UCLA), Terrence Malick (AFI) and Ang Lee (NYU), to name a few. But with the rise of digital cameras and the internet from the early 2000s to today, along with the rise in tuition costs, the value of these institutions has faced increasing scrutiny.

Why Film School Still Matters

Full disclosure: I never went to film school, but I have taught at one - which, in the end, might be the better education. To learn is one thing, but to teach is to reckon with what you think you know - to announce your beliefs to an audience of inquisitive students, then watch those beliefs wobble under scrutiny. That, my friends, is an education.

One thing I thought I knew prior to teaching was that film school was a waste of money. Truth be told, I was never much of a “school” person to begin with. My young mind was always crackling with extracurricular creative interests - playing in bands, cranking out zines (it was the ‘90s), and of course, watching tons of movies. I was a firm believer in learning by doing, and my (hazy) vision of film school was of students dissecting films more than making them. Film school, it seemed from the outside, was an ersatz simulation, and a cripplingly expensive one at that. In the real world, I reasoned, showbiz was an apprentice system, trial by fire - they paid you to learn.

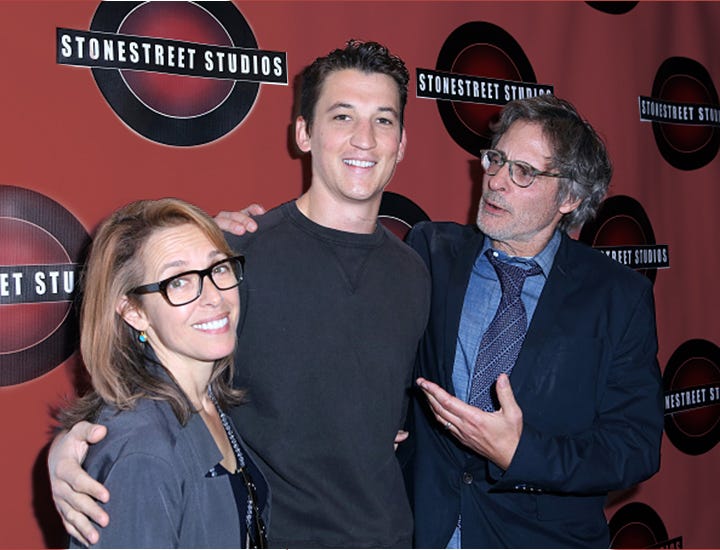

In the summer of 2021, I made a short film. After posting a few production photos online, I got a call from director Alyssa Rallo Bennett, the co-founder (along with husband Gary O. Bennett) of Stonestreet Studios, one of NYU Tisch Drama’s residency programs. She invited me to teach classes in the fall. Additionally, I would serve as a writer-director in residence, churning out short scripts and series and producing them on a rapid schedule. It was a daunting challenge, and an incredibly lucky opportunity. I jumped right in.

Stonestreet was the first screen acting residency in the nation, and remains the only film program affiliated with a degree-granting institution where students actually make festival-grade movies in class. Among their 7,500 alumni are actors Miles Teller, Idina Menzel, Rachel Sennott, Danny Ramirez, Rachel Brosnahan, Jack Quaid and Nik Walker, to name only a few.

Unlike most traditional film programs, where students wait years to direct a project or touch equipment (if ever), Stonestreet prioritizes hands-on learning from day one, with many classes serving as a sort of “bridge” from academics to professional set life. While teaching scene study, screenwriting and development classes, I’ve witnessed the benefits of rigorous deadlines and imposed collaboration. While collaboration can certainly take root outside of film school, it can be extremely challenging to find people with compatible sensibilities, work ethic, and vision. When forced to work with others on tight deadlines, incredible things can happen. In an average three-hour class, we film three to four scenes, while most short films need to be fully shot in four hours. The pace is intoxicating for students and myself alike - reorienting us away from fretting over the outcome and toward a love of the process.

“The aim of education is the knowledge, not of facts, but of values.” - William S. Burroughs

More than any particular lessons, a formal film education can instill values that are hard to come by elsewhere: collaboration, camaraderie, resilience, and resourcefulness. It provides an environment where trial and error are encouraged, failure is part of the curriculum, and lifelong creative partnerships can form.

Film schools are far from perfect. In the United States, they are often expensive as hell. And yes, many programs are subpar. But for those who find the right one - or make the most of the one they attend - the value is undeniable, especially for those who are creative, but not especially self-motivated.

To discuss the enduring value of a formal film education, as well as this week’s Underexposed pick, Rain Without Thunder (1993), it was my pleasure to chat with writer-director Gary O. Bennett and director-producer-actor Alyssa Rallo Bennett.

Where to Watch Rain Without Thunder (1993)

News Reel

Physical Media is Officially Back, declares Kate Lindsay on

. “Those movies and TV shows that you're watching on Netflix and Amazon, they're going to disappear.”My Valentine’s day movie rec: Heart Eyes! It’s a really fun studio movie, you guys. If you like slashers or romcoms, this one is both. The script is funny, sharp and the actors are ridiculously charming. Check it out.

“We are at a very serious crossroads right now. We can either fight to revive culture or we can just put civilization to sleep.” Mo Diggs explores why “Human Mediocrity Will Pave the Way For AI Supremacy.”

That’s a wrap for the free version. Beyond the paywall, Gary and Alyssa share their Underexposed Guest Movie Picks.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Underexposed to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.